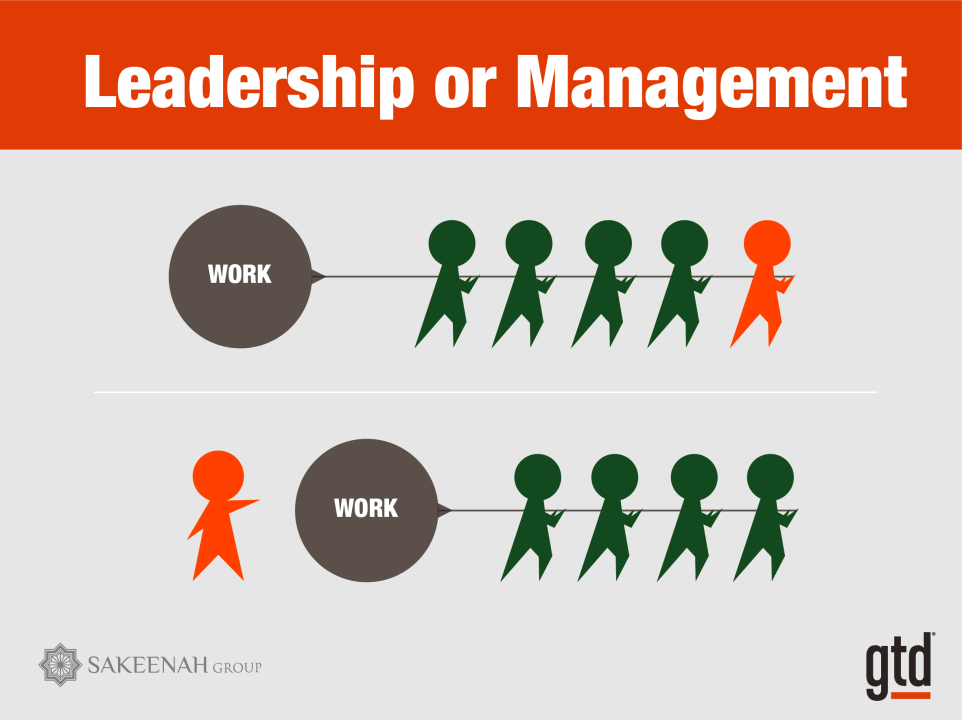

Leadership or Management?

There is a big difference between leadership and management in the world of business. Leaders in an organization have a clear vision of where they want their business to be in the future, are focused on that future, with successful leaders able to communicate their vision downwards into their organization, changing the culture of their business and getting employees to buy into it. Managers on the other hand look for rational ways to translate a company’s goals into reality and focus on efficient ways to deliver on those targets. Put simply, a leader in a business thinks big and ahead while a manager implements a vision given by someone else, quite often a leader.

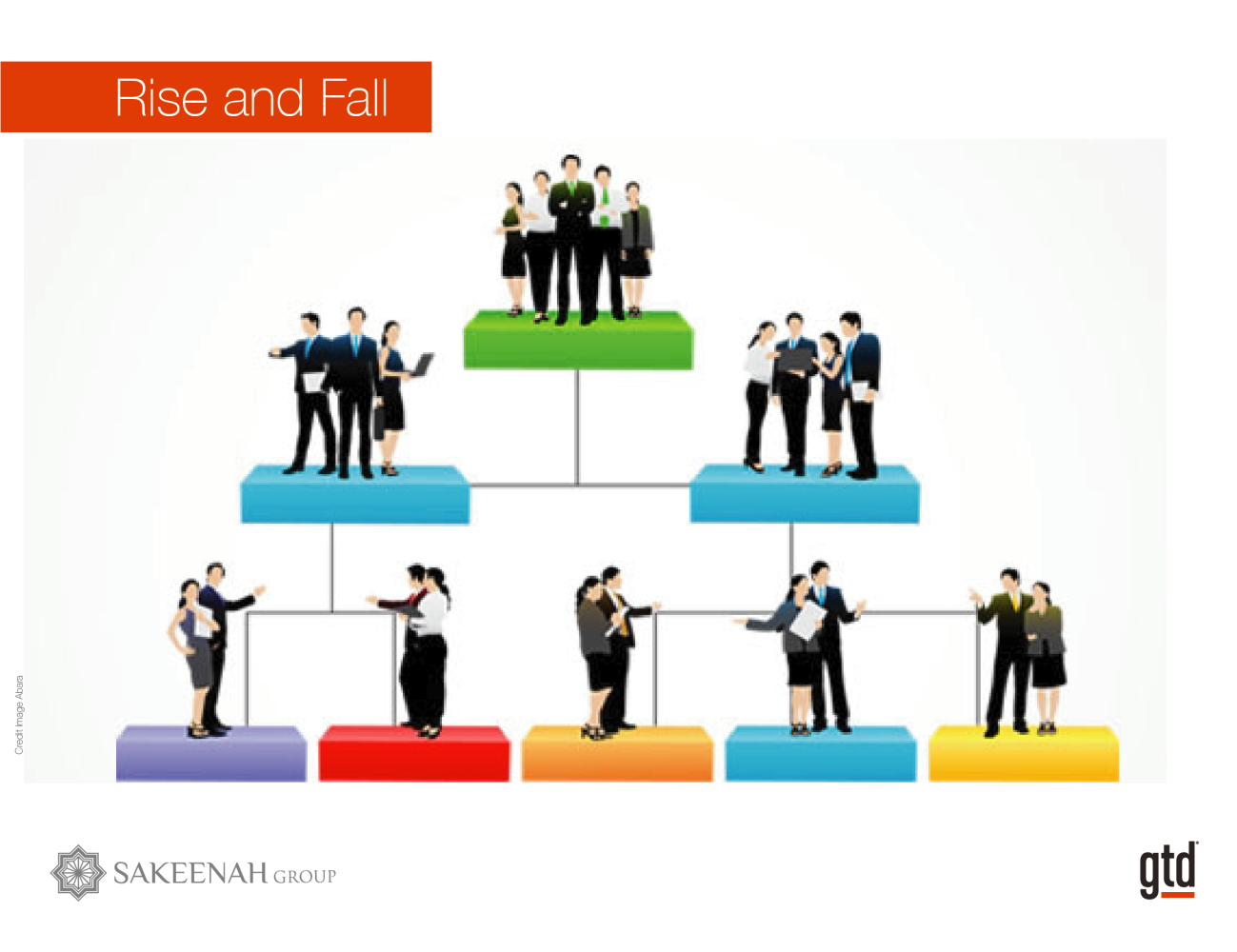

The rise and fall

The story of how an organization clinging to a management style as opposed to a leadership one at the top is a familiar one: a business expands and becomes diversified reaching a fairly dominant position in the market with impressive growth and profits. This is where the problems start coming in: to cope with its large, diversified structure it starts hiring and promoting managers, not leaders, to handle its growing structure. With a managerial culture ingrained at the top, decision-makers within the organization starts taking its market position for granted. A position which can be short lived. In the short term, at best, a managerial style of running a business can maintain (not grow) a business, but in the longer term, it is a recipe for losing value. This is for two reasons.

Top management is increasingly focused inwards, with performance gauged on purely internal factors like cutting costs and constantly rationalizing the company structure. Within such a framework, top management starts ignoring its employees who, rather than being convinced to imbibe and push forward the company’s vision and values, are simply expected to follow orders.

The result of employees not being won over, not sharing in the goals of the company, and not placing much trust in top management, is high rates of labour turnover. This is already a problem with some companies in the ICT sector in Mauritius reporting annual turnover rates as high as 11 percent. In contrast, a study of 4,811 employees in India found that companies whose employees said had a strong leadership culture had a turnover rate of 8.5 percent, compared to the 36.8 percent turnover rate where employees said leadership culture was poor. Where a business is unable to retain its best-performing employees, it is headed for trouble.

The other problem is that a managerial style emphasizes stability and continuity at the expense of innovation and creativity. Business with such a style predominating suffers from ‘analysis paralysis’ where a top-heavy management moves slowly and reactively, unable to spot threats and opportunities from changing technologies and dynamic or even disruptive markets or circumstances, ultimately losing out to businesses who can foresee and harness change and attain adaptive advantage. One need only think of the examples of Kodak, Blockbuster, HMV, Jessops with the list going on.

Employees the best ambassadors

The results are different in companies that emphasize leadership – rather than management. The story of Starbucks is a case in point. When its CEO Howard Shultz bought the company in 1987, it had just six stores and 100 employees. Shultz clung to a leadership style of running his company, sharing his vision with his employees to turn them into ‘coffee ambassadors’ educating customers about fine coffee and creating an atmosphere of “wonder and romance in the midst of a harried life”. By 1999, Starbucks had 2,498 outlets and 35,620 employees, with the company’s market value jumping from $0.41 billion in 1992 to $3.85 billion by 1998. A similar thing happened with Japan’s Matsushita Electric, whose former CEO Konosuke Matsushita relied on a mix of profit targets and convincing his employees to share in his vision for his products “to create worldwide prosperity to such a degree that in several hundred years there would be world peace”. He became one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the 20th century. Under his watch the revenue of his company grew by $49.5 billion – bigger than Walmart or Honda.

From “lao huang-niu” to leaders

Nowhere is this difference between leadership and management more exemplified than in the transformation of China after 1978 and its emergence as a global tech giant. Before its opening up to the world economy, business leadership was unheard of in its planned economy. Good businessmen were dubbed “lao huang-niu” (old bulls used for farming), clinging to a managerial style of running enterprises whose responsibility was simply to do what they were told and realize targets set by the government, rather than decide where their enterprises were heading and how to get there. After 1978, the importance of developing a culture of leadership within business was understood with the number of Chinese MBA graduates rising from just 81 in 1991 to 4,185 in 1998. This difference was felt even more starkly in the area of Zhong Guan Cun (China’s ‘Silicon Valley’), where out of the 5,000 private tech firms established there since 1990, 91 percent of them disappeared within five years and only 3 percent of them made it beyond eight years. The leading cause of the demise of those firms was that their entrepreneurs still clung to the old managerial styles of heading their companies, dictatorial, unable to hold on to their employees and unable to adapt, while those that survived would go on to help China emerge as the tech giant it is today.

Crucial time for shift

The transformative capacity of leadership rather than the conservatism of management is something that businesses were looking into before Covid-19 ever appeared. Managerial styles of running businesses were in vogue back in the 1990s when businesses focused on optimizing the workflow across their core processes and organizations, now leadership is needed when businesses are grappling with the rise of new business models, digitization, employee and consumer engagement. In his, The Meaning of the 21st Century, James Martin describes the current era as one that has changed, “the way we communicate and the way we work. It is a period of technological revolution that centers on computers, information and communication as well as multimedia technologies…a period of transition and change to find solutions to the biggest challenges facing humanity”. The more so today, with Covid-19, as businesses across the world struggle with different challenges; from finding new ways to keeping their employees engaged while physically separated on the one hand. According to a global survey of CEOs by PwC, 54 percent of African entrepreneurs are more worried about cybersecurity than about the pandemic, to indicate how businesses are facing a multitude of challenges.

And certainly, in Mauritius, the need for a shift towards leadership to re-invent business will be felt as businesses struggle with a slow 4.4 percent economic recovery this year while worrying about falling demand, reduced cash flow, foreign exchange fluctuations, disrupted supply lines, production delays and the need to modernize their enterprises. The big problem is that as a study commissioned by the Mauritius Research Council found, most heads of the 123 enterprises (78.9 percent in the private sector) – 65 percent – said that they valued their organizational abilities as their greatest strength with just 44 percent saying that they inculcated a participative organizational culture. In short, the vast majority still think like managers, not leaders.

And at a time of crisis that we are, it is crucial for a shift towards leadership style, towards empowerment and growth of employees, inspiring employees to work for a common vision and goals and towards a culture to adapt and tap on the opportunities that will surface within the uncertain and challenging environment in which we are currently living.

Swadeck Taher OSK is a Chartered Accountant (ICAEW) and a Chartered Marketer (CIM) running businesses and coaching, consulting, mentoring CEOs and entrepreneurs ranging from startups through family businesses to established top 100 companies in Mauritius. He enjoys sharing the expertise he developed over the last thirty years at senior leadership/directorship level with his clients, business partners and other budding entrepreneurs.

Swadeck is also a GTD Practitioner and a Certified GTD Trainer. He helps others experience what the Productive Experience feels like and how they too can savour stress free productivity.

Sakeenah Co Ltd is the only Certified International Partner of the David Allen Company in Mauritius.

GTD® and Getting Things Done® are registered trademarks of the David Allen Company.

Disclaimer: All images are copyright to their respective owners. If any of the images used in this article belongs to you and you wish these removed, please send me a message and I shall oblige.

Explore Our Blog

Discover expert insights, tips, and the latest updates curated just for you.