Business and professional cycling lesson from the first world chess champion (1886)

When Sir Dave Brailsford took over as head of British Cycling in 2002, the team couldn’t boast of anything remarkable. Its last gold medal was in 1908 and the performance of the national cycling team was so poor that bike manufacturers were reluctant to sell them bikes, fearing that the team’s poor performance would affect their sales. By 2008, that same cycling team became a dominant force in world cycling, shattering Olympic records, earning multiple gold medals at the Olympics in Athens in 2004, in Beijing in 2008, and London in 2012. In just a decade between 2007 and 2017 British cyclists had chalked up an impressive haul of 178 world championships, 66 Olympic and Paralympic gold medals, and won the Tour de France five times.

The Theory of Marginal Gains

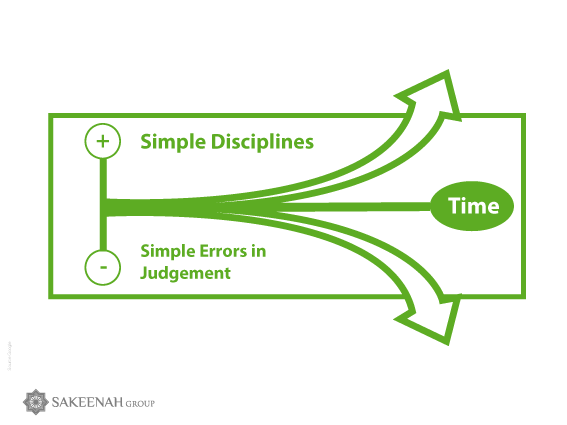

How did Brailsford do it? By focusing on what he dubbed the ‘theory of marginal gains'. In an interview Brailsford outlined his approach: “Aiming for gold was too daunting. As an MBA, I had become fascinated with Kaizen and other process-improvement techniques. It struck me that we should think small, not big, and adopt a philosophy of continuous improvement through the aggregation of marginal gains. Forget about perfection; focus on progression, and compound the improvements”. In terms of strategy this meant that by breaking down every little aspect of cycling and improving each of them by just 1%, the final results would be significantly different. This meant paying attention to details that could otherwise be overlooked. In the case of the British cycling team, this involved things like using indoor suits for outdoor races for greater aerodynamics, measuring how each member of the team responded to workouts, using different massage gels to aid muscle recovery, hiring a surgeon to teach the cyclists how to wash their hands properly to avoid catching a cold, handpicking pillows and mattresses for optimal sleep, tracking the ingredients used in the cyclists’ diet and having the floor painted white to better spot dust that could hamper bike maintenance. In the world of sport, what Brailsford believed had some precedent. Wilhelm Steinitz, who became the first world chess champion in 1886 developed what came to be known as Steinitz's Accumulation Theory which involved the methodical study of the position of chess pieces during a game to steadily accumulate advantages and eventually gain dominance against an opponent. What Brailsford and British cycling had done was take this concept much further.

Marginal gains applied elsewhere

The concept underpinning marginal gains theory can be recognized in other fields such as medicine as well. In a 2010 book, Oxford and Harvard-trained oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee noted how the cumulative effect of small victories in disparate areas of cancer research had paid significant dividends. Lung cancer rates had gone down because of anti-smoking campaigns, better screening techniques meant colon and cervical cancer could be detected earlier, improved chemotherapy had improved survival rates of leukaemia, lymphoma, and testicular cancer patients and breast cancer patients benefited from better screening and surgical techniques. Each of these improvements on their own was insignificant, but Mukherjee argues, cumulatively they had combined to drive the death rate from cancer in the US down by 15% between 1990 and 2005.

Lessons for business

Although it started in British cycling, the Marginal Gains Theory has a lot to teach business too with its notion that small, incremental improvements in a business process added together can lead to significant improvements over time. Rather than a dramatic overhaul, small tweaks and changes mean that each of these changes and their outcomes can be tracked and tested.

For example, 30 years ago American Airlines embarked on a cost-cutting exercise. One of the measures they took was a ridiculous-sounding step of removing just a single olive from meals per customer. That single step ended up saving the airline $40,000 per year.

In its publication "The power of pricing - How to make an impact on the bottom line" PWC argued that businesses should focus on small, but more frequent, 1% price changes rather than raising prices rarely but dramatically. After engaging with pricing specialists from over 500 companies around the world PwC concluded that a 1% change in price can have as much as an 11% impact on profit. The ultimate example of a company that has imbibed the philosophy of marginal gains, however, is Apple. Every time you buy a new iPhone you are not buying something whose technology differs significantly from its previous version, but rather, each new iPhone comes with a few tweaks to improve the customer experience. By frequently coming out with many variations of the iPhone, each a marginally improved version of its predecessor, Apple got the reputation of being the most innovative company globally.

While most businesses are not planning to come out with smartphones each year, they can focus on improvements such as gradually improving pricing structures, optimizing office structure, reducing the frequency of e-mails, reducing the frequency and length of meetings, reducing the price of inputs, or packaging by 1 per cent, reducing employee lateness and improving hiring practices, etc.

Size matters

In theory, the marginal gains approach sounds simple enough. But pulling it off is another thing entirely. First, there is the issue of size. One key ingredient for the marginal gains approach to work is that the whole company should buy into it. In his interview, Brailsford warned, “one caveat is that the whole marginal gains approach doesn’t work if only half the team buys in. In that case, the search for small improvements will cause resentment. If everyone is committed, in my experience, it removes the fear of being singled out – there’s mutual accountability, which is the basis of great teamwork”.

Anthropologist Robert Dunbar showed through his research that organizations of 150 people or less were easier to align to a single objective than larger ones. 150 has come to be known as Dunbar's number. If the whole organization has to share the objective of realizing marginal gains, anthropology teaches us that that’s easier to achieve in smaller organizations. After all, the British cycling team that Brailsford was leading was also a small organization. For larger organizations that means a lot of communicating with employees and putting in place a dedicated focal point/team to look for opportunities and follow up on the implementation of marginal gains throughout the organization. Much along the lines of what PwC found in a study of the digitization of North American companies that showed that the most successful businesses had a digital champion within the management of their organization.

Marginal improvements are about success over the long term, and small improvements may not be dramatic or even noticeable immediately. That means inculcating a strategy of patient improvement, and a vision for the long-term, within the senior management of the organization. A strategy centred around marginal gains is a marathon, not a sprint. And that sometimes, the best strategy might not be to think big, but to think small.

Swadeck Taher OSK is a Chartered Accountant (ICAEW) and a Chartered Marketer (CIM) running businesses and coaching, consulting, mentoring CEOs and entrepreneurs ranging from startups through family businesses to established top 100 companies in Mauritius. He enjoys sharing the expertise he developed over the last thirty years at senior leadership/directorship level with his clients, business partners and other budding entrepreneurs.

Swadeck is also a GTD Practitioner and a Certified GTD Trainer. He helps others experience what the Productive Experience feels like and how they too can savour stress free productivity.

Sakeenah Co Ltd is the only Certified International Partner of the David Allen Company in Mauritius.

GTD® and Getting Things Done® are registered trademarks of the David Allen Company.

Disclaimer: All images are copyright to their respective owners. If any of the images used in this article belongs to you and you wish these removed, please send me a message and I shall oblige.

Explore Our Blog

Discover expert insights, tips, and the latest updates curated just for you.